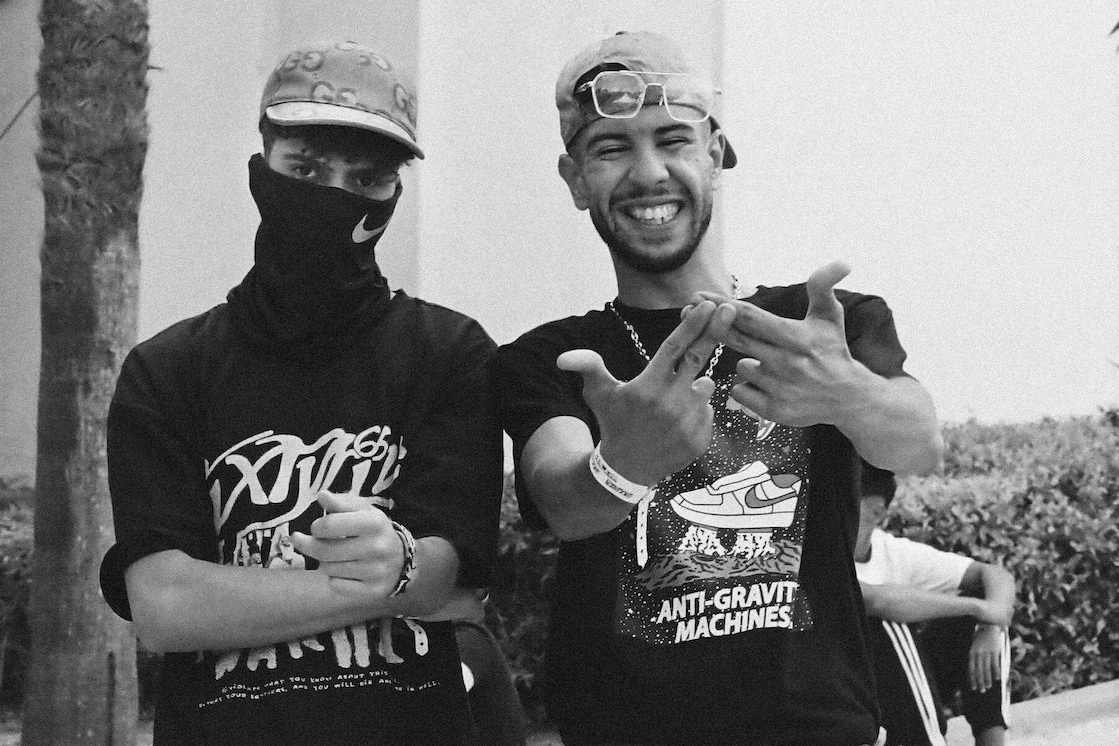

Egregore Festival, Casablanca, 202521 Images

In 1985, Morocco-born, Lyon-raised rapper Shams Dinn moved to Paris in order to pursue a career in music. Performing at a time when hip-hip in anything other than an American accent was practically unthinkable to most audiences, Shams Dinn’s Arabic lyrics immediately stood out. His 1987 single “Hedi Bled Noum” lit up dancefloors across Europe, and the pioneering rapper described himself as a “positive light for Arabic immigrants living in France”. But, when it came time to release his debut album, Shams Dinn faced backlash.

As much of western media was swept up in a wave of Islamophobia in the run-up to the first Gulf War, Shams Dinn’s label presented him with an ultimatum: translate your lyrics into French, or the record gets shelved. Although Shams Dinn chose the latter, four decades later his vision for a thriving Arabic hip-hop scene reached fruition with Egregore Festival, taking place in Casablanca, Morocco last month (26-27 July).

However, Shams Dinn wasn’t the first Moroccan rapper – that accolade goes to Morocco’s so-called ‘answer to James Brown’, Bob Fadoull, whose 1985 single “3ARMNI NENSA” (“I will never forget”) is widely recognised recognised as the first Darija (Moroccan dialect) rap record. “‘3ARMNI NENSA’ was a milestone moment in the history of Moroccan hip-hop,” says creative platform and Egregore founders DOSEI, who timed the festival’s second edition to align with the 40th anniversary of the record. “We felt it was important to acknowledge that legacy, and to position this festival as a continuation of that journey – one that connects generations through the power of expression.”

Featuring 45 rappers from across Morocco’s now-thriving and diverse hip-hop scene, as well as a breakdancing and graffiti events, the coming-of-age festival fittingly took place in Sacre-Coeur Cathedral in Casablanca – a former Catholic Church that was deconsecrated and converted into a cultural centre alongside Morocco’s independence from the French Empire in 1956. “This year marked Egregore stepping out of the underground, uniting huge stars like ElGrandeToto and MADD with the younger generation of rappers,” says Swedish cinematographer and photographer Christine Leuhusen, who documented the event. “You can walk through the streets of any Moroccan city and spot a DOSEI tag and people will immediately be able to read you as part of the community. There was a communal identity and ideology of sharing that permeated the festival.”

Leuhusen spent a summer working at the Border Independent Arts Factory in Tangiers in 2015, and it was this experience that eventually led her to fall in love with the country’s hip-hop scene. ISSAM’s 2019 Moroccan trap mega-hit “Trap Beldi” and associated creative platform SOMNI CULTR, which aims to uplift North African music and fashion, formed big draws for Leuhusen, arriving at a time where local Moroccan artists began utilising social media to reach international audiences. But this fierce creative identity wasn’t born overnight.

“Hip-hop faced a lot of resistance in its early days – especially in a conservative society, people who wore baggy clothes or expressed themselves through rap were often seen as outsiders, sometimes even treated as if they were insane,” explains DOSEI. “It wasn’t just about the music – it was a clash of values, of generations, and of identity. It wasn’t really until the late 2000s that we started seeing a shift as society began to slowly open up to the idea that hip-hop, like any other genre, has a legitimate place in the cultural landscape.”

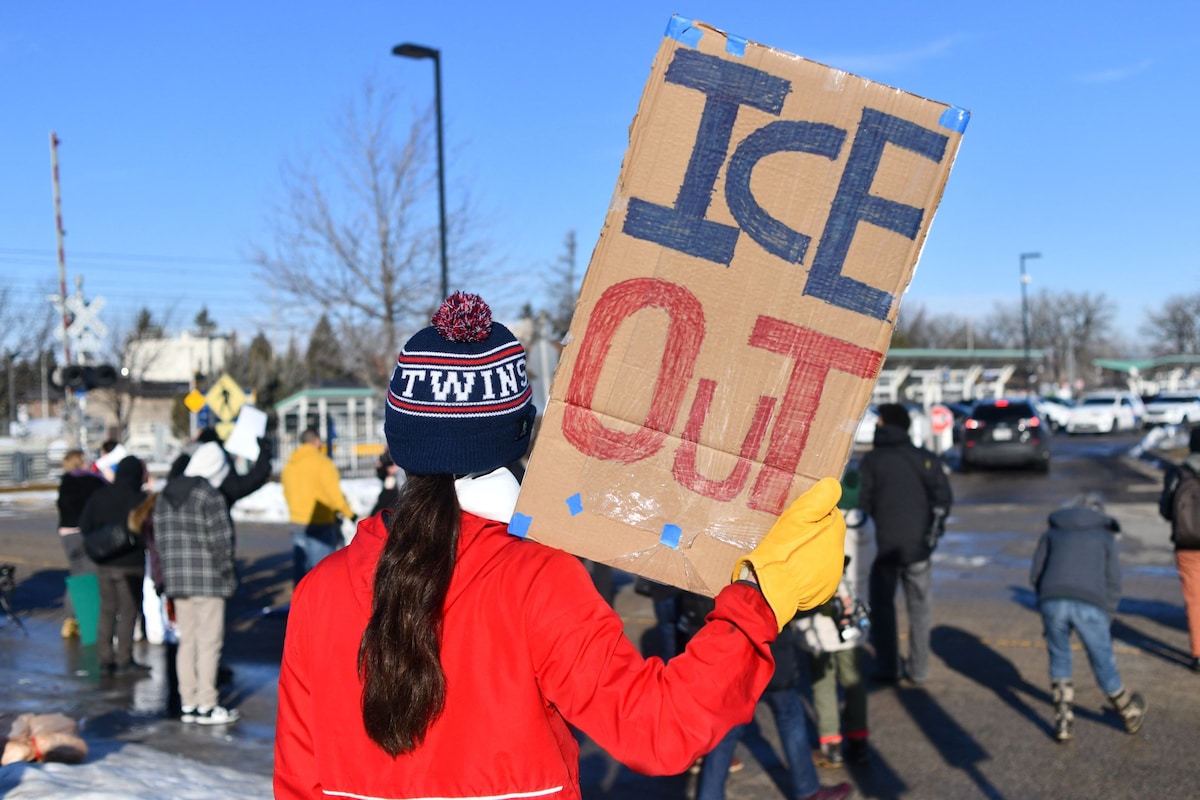

Today, Moroccan rappers are no longer swimming against the tide, but rather actively articulating a cultural identity independent of the living memory of French colonialism. “I spoke to GHVLI, a 21-year-old rapper from Fès, about the need for Moroccan-owned cultural spaces,” Leuhusen recalls. “He highlighted how, too often, venues are still branded with ‘French Institute’ or ‘American Arts Center’. For the youth in Morocco, and all over the world, rap music is a way to address and express the issues and struggles one faces. If the scene is branded by former colonisers, how can they have a voice?”

Elsewhere, the festival featured performances from Rabat’s Fake Gang, whom, in collaboration with DOSEI, organised the NAB Convoy in honour of the group’s late founder NAB Fake in March of this year, delivering food and medical supplies to communities struggling with the aftermath of Morocco’s 2023 earthquake; as well as the ‘Queen of Moroccan Rap’: Khtek. “When Khtek took the stage in front of a Palestinian flag, it was absolutely electric,” says Leuhusen. “The women in the audience gathered and went up the first row, holding space. It was a pure moment of sisterhood and freedom that I will keep with me for a long time.”

Egregore Festival founders DOSEI, however, hope that this landmark event is just the start of a bright new future for Moroccan creatives. “One of our core intentions with Egregore is to set an example that can inspire the creation of more festivals and platforms dedicated to the culture,” they explain. “By giving people a stage, we’re not only validating their work but also creating bridges between generations, styles, and local communities. Our hope is that Egregore can act as a catalyst – one that encourages others to invest in and uplift the full spectrum of talent that exists in Morocco.”

If Shams Dinn saw himself as a leading light of Arabic immigrants living abroad, then this torch has well and truly been passed to the new generation of Moroccan artists who are making rap music to uplift their communities on their own terms.

Catch a closer glimpse of Egregore festival with Christine Leuhusen’s photographs in the gallery above.