It’s a sticky summer’s evening in Peckham, and Folk of the Round Table is just about to begin. The weekly music night, which has been going on since 2018, is open to all to come down and sing folk around the circle. The crowd is overwhelmingly young.

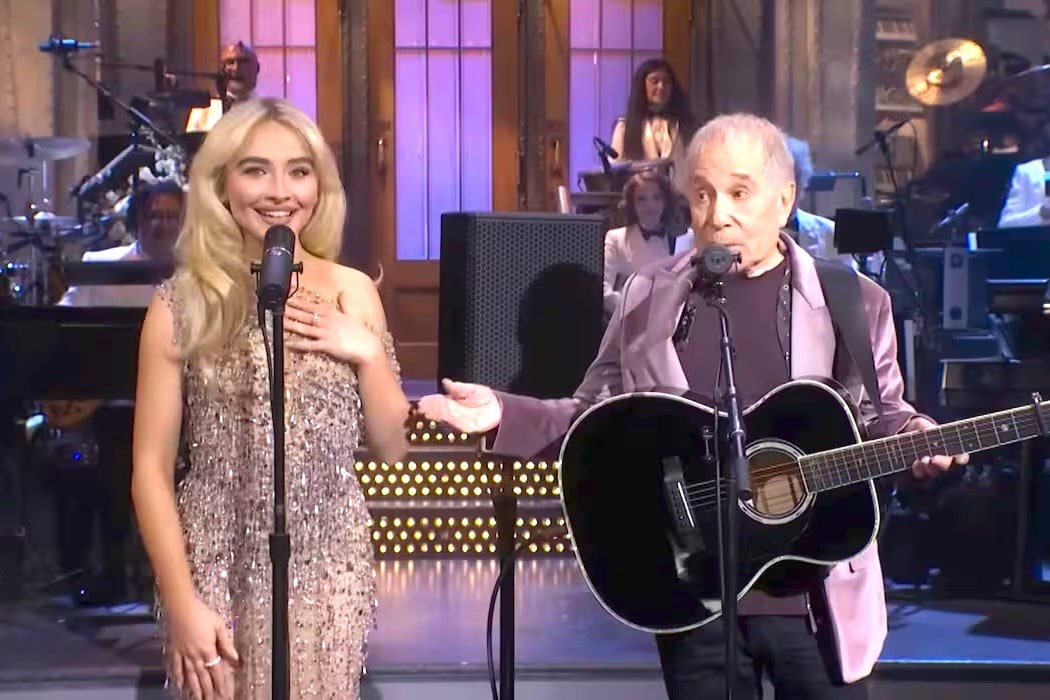

Folk has arguably not been this visible and popular since the mid-20th century. 2025 alone has seen the release of Bob Dylan biopic A Complete Unknown (and a subsequent skyrocket of streaming of Dylan’s tunes); folk-pop artist Myles Smith win the BRIT Rising Star Award; Sabrina Carpenter duet with Paul Simon on Saturday Night Live; and Noah Kahan sell 65,000 tickets to his Hyde Park show.

Folk’s influence is also permeating the sound of other popular artists. Wolf Alice’s krautrock single “White Horses” shares acoustics and harmonies reminiscent of 60s folk-rock; Geese’s summer anthem “Taxes” unites rock with folk for a yearning protest song; Ethel Cain’s recent album Willoughby Tucker, I’ll Always Love You, calls upon traditional folk for mesmerising storytelling. Gen Z pop favourites like Phoebe Bridgers, ROLE MODEL and Djo, also draw on folk in their music. Last year, Spotify’s editor for acoustic programming announced there was “a fresh wave of relevance sweeping through Gen Z that is hard to ignore.”

This revival should not come as a surprise. Folk singer Helena Day, co-host of this night’s Folk of the Round Table session, explains that folk’s popularity has grown in tandem with technological advances since the days of the Industrial Revolution. “As people moved from the countryside and into cities and factories, there grew a nostalgia for simpler times, a leaning towards a pastoral aesthetic, and a renewed fascination in British folk and pagan culture, which led to the trend of folk song collecting.” The 60s saw the birth of the first folk revival, with the music going “hand in hand with the hippie counterculture,” Day says. Today, “in our current dystopian internet age”, both traditional folk and a pop-facing adaption of the genre are being embraced by young people.

“I wonder if young people are using folk as a medium to reject the modern way, to reject capitalism,” musician Billie Marten muses. With her fifth album Dog Eared released weeks ago to critical acclaim, Marten, who has been creating folk music for over a decade, is something of a pioneer of the folk revival for her generation. “The sound of it, the material, the wooden nature of everything, the quality of the storytelling… As a young person, that’s all you long for,” she continues. In a time of unprecedented financial hardship and economic instability, it tracks that young people are finding both solace and escapism within the sonic softness of folk. Difficult times lead to folk: for example, pop doyenne Taylor Swift wrote and released folk albums folklore and evermore during the Covid-19 pandemic, as inspired by the loneliness of lockdown.

Gen Z is moving into an era where we value artists who feel relatable authentic, and honest

– Rae Foster, The Other Songs

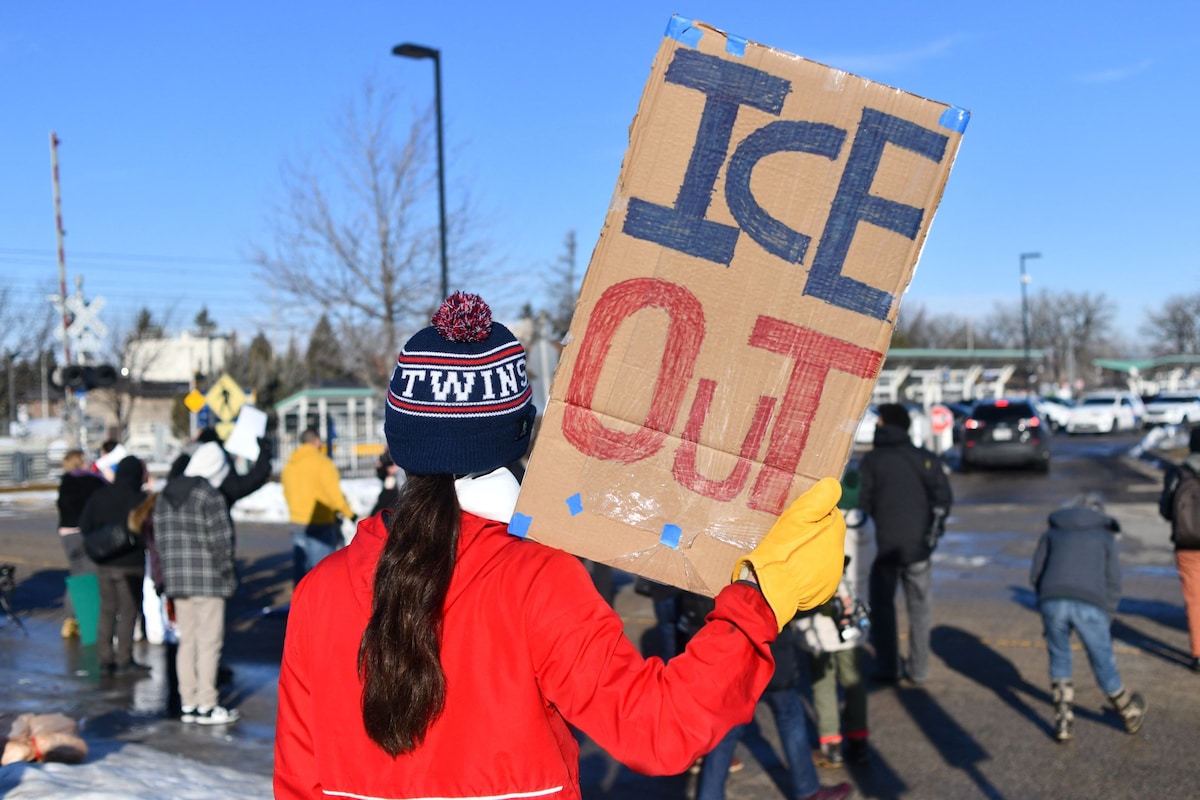

With the zeitgeist tinged with pessimism, it’s entirely understandable that young people are gravitating towards a genre that has championed the underdog and romanticised the downtrodden. “Gen Z is moving out of the age of idolising an image and into an era where we value artists who feel relatable, authentic, and honest,” says Rae Foster, creative assistant at music label The Other Songs.

So it’s perhaps no surprise that in 2025, folk music as both a genre and a community is rapidly increasing in popularity, especially among young people. Reminiscent of the pacifism of the hippie counterculture, folk singer Mon Rovia reflects Gen Z’s sympathy and solidarity with Palestine in the lyrics to his song “Heavy Foot”, in which he sings “Calling it a war, not a genocide”. At her Lyric Theatre gig last year, indie-folk singer Julia Jacklin spoke to her audience about Palestine between songs.

Sat at Folk of the Round Table, listening to this modern community sing and laugh together, it occurs to me that folk’s resurgence feels like being a small part in the lineage of the human experience. “On a wider level, it’s a testament to the fact that the link between music and community is inherent,” folk singer Maria Mihailik, co-host of the night, tells me. “It’s historically been a collective activity at its core. I see it in many ways as the music of the people.”

This Gen Z-led revival feels like a passive form of resistance against our disconnected, individualistic society in the form of community. The times may be a-changin’, but our coping mechanism, clearly, hasn’t. Is folk the original counterculture, I ask Marten? “Yeah,” she says. “We’re going back to the source.”