Editor’s pick — Accessory quick take: key highlight (movement/specs for watches, materials/finish, limited run, pricing tier) in 1–2 lines.

This has been a particularly great year for history-shaping horological discoveries. The sale of the J. Player & Son’s Hyper-Complication at Phillips Geneva went extraordinarily well, achieving CHF 2,238,000, or just shy of $2.8 million in US dollars. That’s on the heels of the sale of a pocket watch by Derek Pratt for Urban Jürgensen last year for the equivalent $4.6 million. Each of these watches was a type of era-defining piece, for the tail end of the heyday of English complicated watchmaking and for the rebirth of the independent scene. But they were also known watches. There’s something particularly captivating about discoveries.

The Patek Philippe John Motley Morehead Double Movement Minute Repeating Split Seconds pocket watch, which was previously unknown to the public. Photo courtesy Sotheby’s.

The collection of late, great American horology lover Robert Olmsted, which is being offered by Sotheby’s on December 8 in New York, changes our understanding of horological history than any revelation in recent memory. We covered the announcement of the multiple previously unknown Patek Phillipe watches and a previously unknown Patek desk clock that technically outshines similar ones made for James Ward Packard and Henry Graves.

These aren’t just unknown; they’re technical marvels that weren’t documented outside of Patek Philippe’s books. While they’re not wearable in the same way a Patek 1518 is, they’re the kind of revelation that the old guard of collecting (and some of the new) would die for.

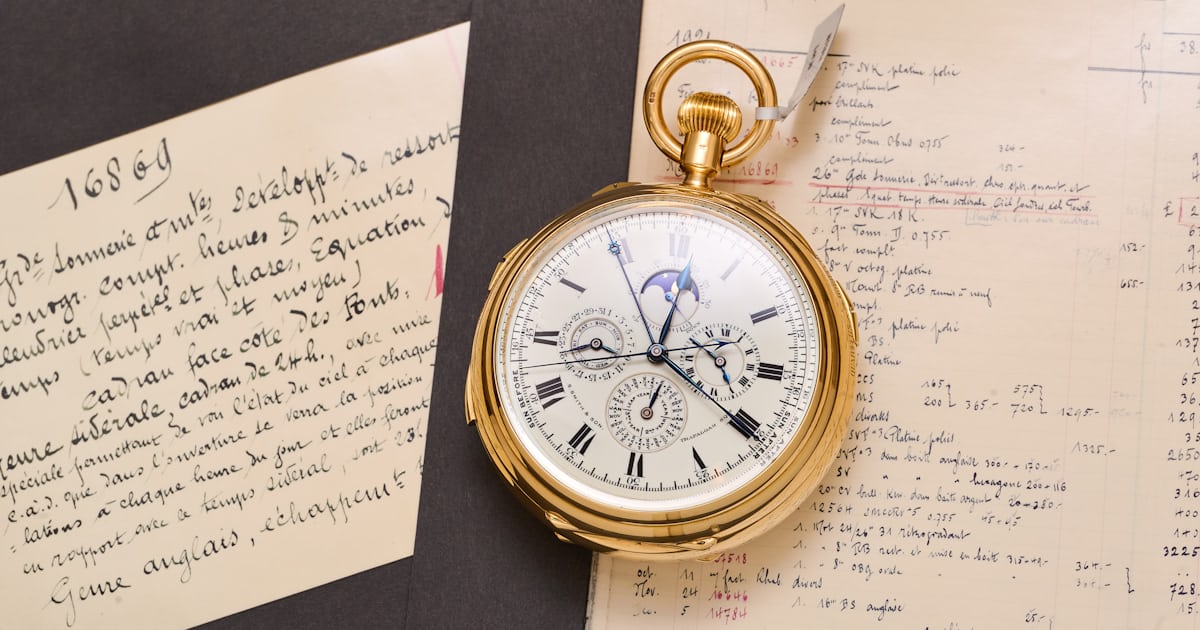

J. Player & Son’s Hyper-Complication at Phillips Geneva. Photo courtesy Phillips.

Credit where credit is due, I was jealous of our colleagues at Watches by SJX, who got to see the J. Player & Sons and wrote an excellent story on the meaningful nature of that watch. It’s inspired me to do something similar with the Grosse Pièce, albeit less technical. The watch, named as such (or “Large Piece”) by the watchmakers who worked on it, is tied with AP’s “Universelle” as the most complicated pocket watch ever produced and the most complicated pocket watch from the brand in private hands.

It’s also the only pocket watch in AP’s history to feature a sky chart complication and the only known tourbillon pocket watch from this brand in this era. While the Universelle sits at the literal center of the Audemars Piguet museum, this watch is up for sale, with an estimate of $500,000 to $1,000,000.

The Creation of the Grosse Pièce

To put the watch in lineal context, Audemars Piguet’s Universelle preceded both other watches mentioned so far, made in 1899, with a different suite of 19 complications. The J. Player & Sons Hyper Complication came next, starting as an ébauche from Vallée de Joux complications specialist and etablisseur Louis Elisée Piguet. The base movement was delivered on December 9, 1902, to Capt & Cie. in Le Solliat, which was the Swiss partner of London-based Nicole, Nielsen & Co..

The letter, ordering the Grosse Piece. Photo courtesy Sotheby’s.

In 1914, the prominent London-based watchmaking firm S. Smith & Son contacted Audemars Piguet’s London agents Guignard & Golay to request a special watch with celestial complications for one of their most important clients. It makes sense, as the Vallée de Joux had built a reputation (and maintains one) as the “Valley of Complications.” Audemars Piguet was one of the only firms capable of tackling such a complicated project within the valley.

The project would take seven years to complete and required some of the best minds from within and outside the brand. A note in AP’s archives, filed January 26, 1915, gives a frame of reference for possible unique astronomical complications “falling under the SSS request” – or S. Smith & Sons.

The note suggests further study of potential complications, some of which would ultimately be incorporated into the watch, and many that were not, like a compass, the 12 signs of the Zodiac, the solstices, and the equinoxes. In short, the door was open with a remit to make an incredibly complicated, celestial-minded pocket watch.

A ledger from Guignard & Golay. Photo courtesy Sotheby’s.

While it’s unusual for brands in the modern era to publicly admit to using outside contractors to facilitate such important projects (one notable exception being the recent clock with automaton by Vacheron Constantin and François Junod), here, AP turned to the same system of experts that created the Leroy 01, the most complicated watch in the world at the time, in 1901. The system, called établissage, relied on using individual producers in their area of expertise. The Grosse Pièce, therefore, called upon the following people (according to the archives of AP, shared by Sotheby’s).

A List of Makers Who Contributed to the Making of the Grosse Pièce

- Charles Piguet, Le Brassus – Base movement or ébauche

- Ami Meylan, Le Brassus – Jewelling

- Marius Capt – Spiraling

- Henri Golay, Le Brassus (at Audemars Piguet) – Escapement

- Jules Cesar Capt of Capt & Co., Le Solliat – Tourbillon

- Sons of Louis-Élise Piguet, Le Brassus – Chiming complications

- Léon Aubert, Le Brassus – Astronomical, perpetual calendar and equation of time

- Alphonse Meylan, Le Brassus (at Audemars Piguet) – Time setting

The list is a “who’s who” of some of the era’s watchmaking greats, though as always in the Vallée de Joux, the common last names can trip people up. Charles Piguet and his father, John-César Piguet, also created the ébauche for the Leroy 01 in their workshop in Le Brassus, where AP is still headquartered. The other Piguets on the list, the sons of Louis-Élise Piguet, were complications specialists, and in addition to being talented with perpetual calendars, they were masters of sonneries. Henri Golay is listed in some places as having been a teacher to Louis-Élise Piguet himself and was responsible for fitting the tourbillon to the watch, which was omitted from the ébauche delivered to AP.

The Leroy 01, which sits in the Museum of Time at Palais Granvelle in Besançon, France, was also created by some of the watchmakers who made the Grosse Pièce. Photo courtesy FHH.

Arguably, the most critical part of the watch—as it was the express request of the client—was the astronomical complications that were left to Léon Aubert. Much of Aubert’s life story is known thanks to documentation by noted Vallée historian Daniel Aubert (whose four volumes on the valley are must-haves for history lovers, though only available in French).

Aubert was responsible for the astronomical complications on another notable English-delivered, Swiss-made watch, the Dent 32’573 (sold at Sotheby’s in 2020 for CHF 800,000), which formerly belonged to notable Boston-based collector of important English watches Elliot Cabot Lee (who died in 1920). Cabot Lee was essentially the Henry Graves or James Ward Packard of English watchmaking commissions at the time; however, many of his watches still relied on Swiss work and parts.

The Dent 32’573, which sold at Sotheby’s in 2020 for CHF 800,000. Photo courtesy Sotheby’s.

Aubert died the same year as Cabot Lee, after nearly 50 years working in his workshop (established in 1872) in Le Brassus. During his lifetime, he invented a new mechanism for the equation of time complication, which he sold to brands like Patek Philippe. That included Patek Philippe’s watch no.111’505 and Patek 198’023, made with his apprentice Paul Auguste Golay. He then created another such mechanism for Golay Fils & Stahl, numbered 28,432, which was sold at Sotheby’s Geneva in 1992. That watch was made for the Maharaja of Patiala and featured a perpetual calendar, minute repeater, sunrise and sunset indicators, and moon phases. In short, Aubert was the man for the job.

The movement (number 16869) was 26 lignes, or approximately 58.65mm, and was finished in a more traditionally English style with a ¾ plate. The Swiss used their favored Swiss lever escapement (rather than the detent “chronometer” escapement preferred by the English). Before officially completing the watch, Audemars Piguet displayed it at the Geneva Watch Exhibition in 1920, one of the earliest versions of what would become fairs like Basel or Watches & Wonders. The watch lacked some finishing and featured a different sidereal time dial, which was later replaced with an Arabic numeral dial, improving legibility.

The near-complete version of the Grosse Pièce. Photo courtesy Sotheby’s.

The under-dial movement. Photo courtesy Sotheby’s.

A photo of the Geneva Watch Exhibition in 1920. Photo courtesy Sotheby’s.

In 1921, the watch was finally delivered to S. Smith & Sons, who signed the dial, adding “Trafalgar Square.” The bezel interior is hallmarked FT for Frederick Thoms, with London hallmarks. Thoms was a noted English casemaker specializing in top-tier complicated cases. The massive 18k gold case features sliders to set the striking mode from on to silent, from hours to hours and quarters, or to chime the minute repeater. The remaining protrusions on the case are switches that aid in setting the watch.

The Audemars Piguet ‘Grosse Pièce’

From there, the Grosse Piéce would largely disappear from public view, only appearing in the November 19, 1921, issue of the London-based publication The Graphic. Horological historian and writer Gisbert Brunner would later rediscover the piece while researching for an article in The Horological Journal in 1990 and was later connected with its owner, Robert Olmsted, who allowed photography for Brunner’s 1993 book with Christian Pfeiffer-Belli and Martin K. Wehrli titled Audemars Piguet.

The receipt for the sale to Robert Olmsted. Photo courtesy Sotheby’s.

Where the watch was from 1921 to 1970 is unclear, but according to a handwritten receipt, Robert Olmsted bought the Grosse Pièce from Sydney (“Sid”) Rosenberg, confirming the sale of $23,350 in March of 1970. The watch comes a suite of paperwork and other items bolstering its provenance and heritage. The fitted wood box features a plaque labeled Astronomical Watch by S. Smith & Son Ltd., London. There is an album assembled by the former director of the Musée Atelier Audemars Piguet, Martin Werhli, who co-authored the 1993 book on Audemars Piguet. That album has copies of the workbook records, Registre d’Établissage (Establishment Register), and a copy of two documents referring to the inspection of the jewelling. There’s also a photocopy of the invoice from 1921, to Guignard & Golay, London, the agents who ordered the watch. Not really necessary, the watch also has AP’s Extract from the Archives, to complete one of the more extraordinary sets I’ve seen with a pocket watch.

In Person

As with nearly every hyper-complicated watch, approaching, reading, or interacting with the Grosse Pièce is an overwhelming experience. The watch measures a massive 80mm in diameter, 34mm thick, and weighs 624 grams. That size (3 ⅛ inches by 1 ⅓ inches and 1 lb 6 oz) is imposing, but understandably legible because of it. Unlike the J. Player & Sons Hyper Complication, which features six subdials, the Grosse Pièce is double-sided, which can simplify its display somewhat. The 19 complications can also be easily condensed into simpler displays (all the functions of the perpetual calendar and moonphase account for six, for instance).

I haven’t shared the complete list of complications yet, which is as follows:

The timekeeping functions: hours and minutes of sidereal time (2), equation of time, and tourbillon regulator. The calendar functions: perpetual calendar, century leap-year correction, day of the month, days of the week, months, a star chart, age calculation, and phases of the moon. The chronograph functions: chronograph, hour recorder, and minute recorder. The chime: “Grande sonnerie” with carillon, “Petite sonnerie” with carillon, minute-repeater, and chiming mechanism with silent mode. Other functions: going train up-down (power reserve) indication)

The front dial, done in white enamel, features Roman numerals for standard or mean time shown with blued spade and whip hands. There are four subdials, all of which are slightly weighted toward the top of the dial. At 12 o’clock, the enameled moonphase subdial features a combined display of the age and phases of the moon, positioned at the top, accompanied by an up/down indication below. At 3 o’clock is the unusual combined 60-minute and 12-hour chronograph counter, which resembles a second time zone indication due to the Roman numerals.

The commissioners of the watch are displayed in the lower half, flanking the months and year in the leap year cycle.

You’ll also see the date and day of the week.

And the chronograph counters at 3 o’clock.

The 6 o’clock subdial displays the months and the timing in the leap-year cycle, while the 9 o’clock subdial shows the month and date. At the edge of the dial, a blued hand capped with a sun indicates toward the outer ring for the equation of time (the difference between mean solar time, which we use daily, and apparent solar time, defined where noon is directly overhead). Apparent solar time drifts throughout the course of the year (around plus or minus 15 minutes), and you can see the scale of whether the sun is direct overhead before or after our mean time.

The rear dial conveys far less information, in some ways, but is far more captivating in others. The sky chart shows a Northern Hemisphere view of the stars seen from London (specifically 51.5072° N, 0.1276° W). If you reference the star chart any time, day or night, the celestial vault shows what would be overhead, with 315 stars and various labeled constellations, painted in gold against a blue enamel ground. For reference and orientation, there are two silvered plaques, Western Horizon and Eastern Horizon, then a gold guilloché surround hiding the portions of the vault that isn’t seen on that day. At the edge of the dial is a 24-hour display for sidereal time. While the front dial seems somewhat like any other grand complication from the era and in many ways timeless, the rear dial looks uniquely like something made in the early 1900s.

A look under the dial, thanks to photos provided by Audemars Piguet during their teardown and study of the watch, reveals a few of the movement’s interesting features. A full bridge holds the tourbillon, unlike the Nielsen type 2 skeletonized half bridge found on the J. Player & Sons. The inclusion of a tourbillon (the only known from AP in this period) speaks to the English audience, which had an appetite for such watches, but, as you can see, the constructors stuck with the Swiss lever escapement rather than the English. The chronograph works are significantly simpler than the J. Player, as well, but you can see (especially on the tourbillon side) that the finishing is equally attentive to English style preferences.

Photo courtesy Audemars Piguet.

Photo courtesy Audemars Piguet.

Photo courtesy Audemars Piguet.

The case, while simple in appearance, is beautifully done by Thoms. Maybe the most captivating is the sound of the chiming complications. I was lucky to get to listen to the repeater, and it’s truly spectacular, maybe one of the best I’ve heard. Sometimes, in a watch this large, the repeater can feel a bit choked off in a tight case, but the large gongs wrapping the 26 ligne movement have adequate space for a large, round, warm sound. Even Sebastian Vivas at Audemars Piguet told me during Dubai Watch Week that the strength and beauty of the repeater absolutely floored him.

Then there’s the provenance. In speaking with Daryn Schnipper, Chairman Emeritus of Sotheby’s Watches, I felt some envy of the time Olmsted came up in as a collector and of his perspective on collecting. Olmsted bought watches young, many of them before 1971, and corresponded with dealers as he bought them from his dorm at Princeton. He quickly became the guy with a collection into which some of the most fantastic watches ever made would disappear.

The two Patek Philippe John Motley Morehead double movement watches, including the double movement minute repeating split seconds chronograph and the ultra-slim double movement minute repeating watch.

The Patek Philippe grande and petite sonnerie clockwatch from John Motley Morehead. Approximately nine-minute clockwatches from Patek are known.

Other items, like the previously unknown double-movement Patek watches and the Patek 10-day desk clock, initially drew more attention, but this watch is an equal masterpiece. Schnipper told me that Olmsted saw himself as a collector, with a pure focus that contrasted with other collectors who had “hoovered up” anything and everything in their path. Olmsted had a passion for chronometry and complications and truly lived with his timepieces.

He kept the Patek desk clock on his nightstand and his pocket watches nearby in the bedroom, winding about a dozen of them every day, timing and tracking their accuracy. A second per day of drift was enough to frustrate Olmsted. But at the same time, the collection was deeply personal, and it seems he didn’t even share them with contemporaries like Seth Atwood or others. There are certainly others like Olmsted out there, but it’s hard not to be jealous of collectors like these in the days of Instagram and ego-driven collecting. However, the discoveries that have come out of the Olmsted collection feel like once-in-a-decade (or less) occurrences, and create the kind of auction worth watching.

For more on the “Grosse Pièce” and other watches from the Olmsted Collection auction, visit Sotheby’s.

Source: www.hodinkee.com — original article published 2025-11-28 16:00:00.

Read the full story on www.hodinkee.com → [source_url]